This is a post from the archives of my former travel blog, UnrealTravels.com. It was published in a variety of places, including the PilotGuides website (which I did some community/forum development work for several years/decades ago). A recent article on Jalopnik about the joyless experience of American Amtrak service lead me to re-publish it.

NOTE: I have not edited this piece since writing it in the lobby of the Atlanta Hotel in Bangkok sometime in 2004. It may have been the romance of the situation, but it appears that I found love in the grimy edges of train transport where others might not get the opportunity to experience that same joy. A product of time or place? Unknown.

I dreamed of riding the rail ever since I was a young child. I collected pieces of model railroad sets – setting them up in my small room – imagining myself one of the passengers. I would lie on the floor with my ear to the ground, watching the toy engine make its circular path around the small track. Only the slight hiss of the electric motor and the scraping of metal tracks could be heard as it whizzed around in endless circles.

Growing older, my fascination with model railroads waned and I begun looking for the real experience. I toured train museums and ate dinner on vintage rail cars converted to rolling dining halls. I rode the subways of New York, Chicago and the trolleys of San Francisco. I had the opportunity to ride the rail from Venice to Florence, Bangkok to Nong Khai and I even had a chance to ride the historical “Death Railway” across The Bridge Over the River Kwai in Thailand. These were all very impressive machines complete with services you might expect to find from a modern railroad enterprise. The convenience and punctuality of these systems left me satisfied, but craving more.

For over a century, the romantic sensation of rail travel has existed. Travel by rail harkens us back not only to the industrial revolution, but also the advent of leisure travel among the upper crust of western society. These magical overland journeys remind us of exotic destinations and a bygone era. There are places around the world, however, where rail travel remains as much a part of the local culture as it is a means to get to a final destination. The aging tracks of Burma are that kind of railroad.

White-gloved service that accompanied The British East India Company is now part of Burma’s history. These days, many travelers choose to ride the “impress the tourists” route from Yangon to Mandalay, where upper class cars contain modern reclining seats, dining cars and sleeper coaches. The less-traveled routes have barely changed since Burma declared independence from Britain in 1948. Since that time, many of the British-built rails have not been upgraded or maintained. When they are, Burma’s military controlled government tends to build them with reused equipment and forced labor. Fatal accidents are common, but reports rarely make it into the state-run media outlets. Unofficial reports tell a rather grim tale of the Burmese railroad system.

Nearly every local person I talked to about the train immediately cautioned me to take the bus or the boat. They said the train was too expensive for foreigners. Their hushed references to government ownership of the railroad sounded more like a silent protest. They told me that the train was slow and unreliable. Having spent 18 hours in the back of a bus from Yangon to Inle Lake, I had a pretty good idea what to expect of slow and unreliable Burmese transportation.

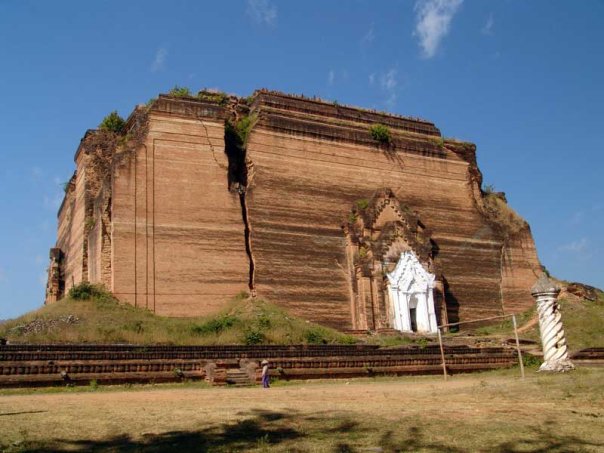

Having spent the afternoon aboard a private charter boat visiting the ancient city of Mingon, near Mandalay, I decided to forgo the traditional riverboat passage from Mandalay to Bagan down the Irrawaddy River. I asked around about the night train from Mandalay. Thinking I could get some sleep on the train, and save the expense of getting a room for the night, I decided to ride the rails.

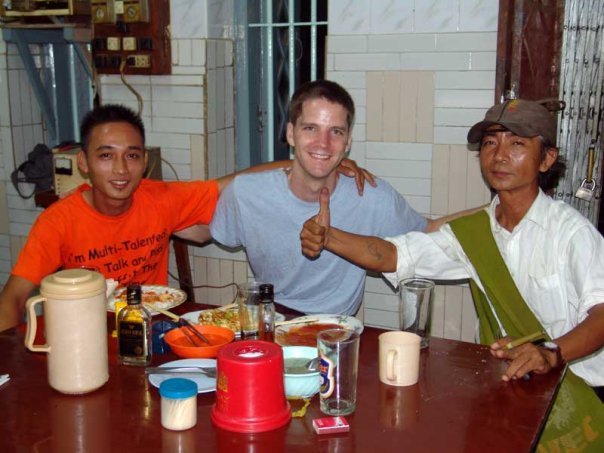

After dinner and drinks with my Burmese friends, they offered me a ride to the train station. I arrived early so I could navigate the maze of a ticketing counter. The depot was dark, all signs were in Burmese and there was very little indication that a train was even nearby. I found the only open ticket counter and managed to mutter out the name “Bagan,” a deserted city, from 11th to the 13th centuries — of magnificent pagodas and temples on the banks of the Ayeyarwady. Bagan is one of the wonders of Asia, ,one that many believe rivals the temples of Angkor in Cambodia.

The ticket agent spoke English just enough to sell me my $9 USD upper class ticket, a ticket which locals pay only $1.50 for. The high ticket prices aim at dissuading foreigners from traveling by train, reserving the seats for Burma’s rich and military elite. I sat and chatted with a group of vacationing monks before making my way to the Mandalay-Bagan bound train.

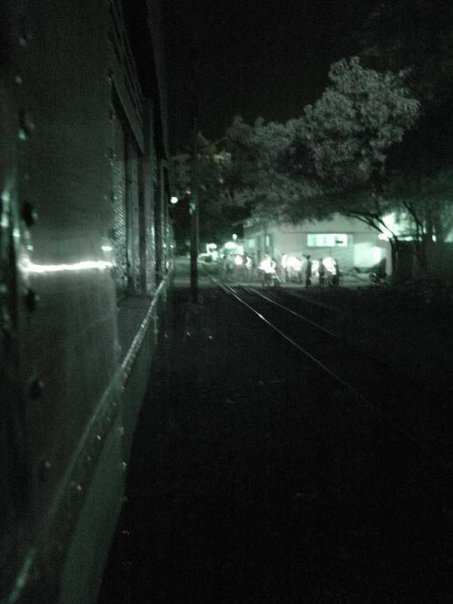

As I walked down the dark platform, I passed a countless number of families that had built make-shift residences along the tracks. The environment felt like a small village – people ate, slept and worked there. The smell of diesel fuel and charcoal stoves hung heavy in the air. Food and drink were traded with the train passengers. As the only foreigner on the train that night, I was more of a curiosity to the hawkers than a potential customer. Seeing that I was clearly out of place, a young Burmese traveler helped me find my rail car in the pitch-black night.

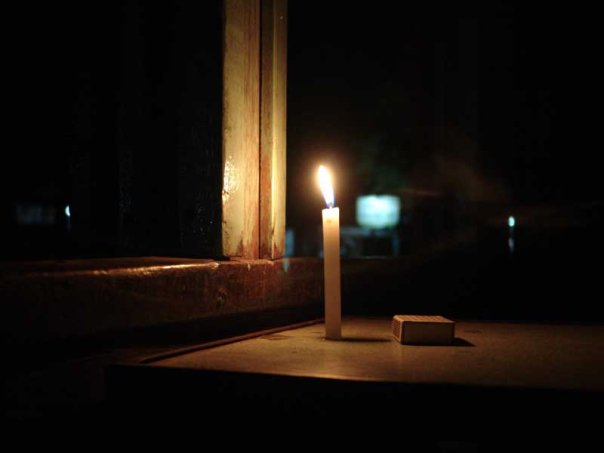

As I boarded the train, I struggled to find a torch in my overstuffed bag. The locals were having just as much trouble finding their seats as I was. Fortunately, the British not only left behind these aging green rail cars but also English seat numbers. Our upper class seats were just as hard as the ordinary class benches, but had a thin fabric covering and pad that made them look somewhat comfortable. The only illumination in the rail car was a single bulb dangling from the ceiling, attached by lose wires, barely making enough light to make itself known.

As I took my seat, I was offered bottled water through the open train windows. The other passengers bought snacks and sometimes entire unidentifiable meals as the train started to slowly fill with local travelers. The family across the aisle from my seat offered me a candle for my table. I lit a mosquito coil in a desperate attempt to discourage the smaller buzzing passengers from feasting on me as their late night snack.

At 10:00, the train blew her whistle a few times to signal our departure. Minutes later, the train lurched forward and pulled out of the station. Through darkness of night, we slowly made are way away from Mandalay. The city lights faded in the distant and was replaced by a shadowy landscape of rice paddies and thatch roof houses. I could feel the countryside passing by, but could see no more than a few inches outside the window. If it wasn’t for the sensation of movement and the click-clackety sounds of steel-on-steel over the rail joints, I might have assumed we were trapped in a dark tunnel.

Further outside of town, the train started to pick up speed. The dangling light bulb became bright as a burning ember. It swung violently back and forth, creating a strobe effect, further enhancing my psychological fear that I was riding this train to certain death. The cars rocked from side to side with fierce motion; the train made back-breaking lunges up and down. I tried to close my eyes, but could only see an image of the train being pulled from a deep ravine below. I struggled to find my rucksack where I had conveniently stored the only device that could save me from death by rail: an inflatable seat cushion.

The nostalgia of riding the rail was now gone, survival mode had become my only consolation. My body curled up like a pretzel, trying to find a spot where I could rest without flying out of the seat. There were times, throughout the night, that the cars rocked so violently I thought they would fly off the tracks. Plunging to the bottom of a dark ravine was not a settling image. During the 8 hour trip I think I had a total of 10 minutes of anxious sleep. In the haze of morning, I sat disoriented trying to figure out how long I had been traveling and if I had reached my final destination. It was a little past 6:00 am, I was alive. The train had followed her rails like she was built to do.

Rather than waking rested and relaxed for a day of temple climbing, I was sure I had a case of vertigo and post traumatic stress syndrome. The memory of riding Burma’s Mandlay to Bagan rail line will not likely fade. Photos and video will never tell the complete story. It’s only through first-hand experience that someone can appreciate what it is like to meet death face-to-face and survive. The next time I travel to Burma, riding the rail will be at the top of my list of things to do.

Text © Michael Kraabel 2004, All Rights Reserved